While tramping through the ruins of Banteay Srei in Cambodia a couple of years ago, I overhead a tour guide mention a Khmer Silk weaving unit in the vicinity. I had heard about this legendary fabric once considered the finest silk produced in the world. The Khmer Rouge, however, cut down hundreds of acres of mulberry trees that fed the worms and destroyed this centuries old craft. Now, only one metric tonne of this golden coloured silk is produced every year. The natural dyeing and weaving of which is known just to a handful of artisans. So this weaving unit, if it was indeed around, was probably one of its kind.

Driving past a signboard marking the land mine museum, we turned into a flooded dirt track that seemed to lead straight into the grey monsoon horizon. Just when the water looked like it was high enough to come through the car doors we saw a surprisingly ornate archway and turned in. In the middle of barren countryside that was once ridden with landmines, we drove through what looked like a village with a thick tree canopy. I didn’t know then that we were driving through a forest carefully grown and a village entirely sustained by of the efforts of one person.

Kikuo Morimoto was a weaver from Kyoto, Japan, who came to Cambodia in 1995 following the legend of a world renowned silk. He found the scattered remains of the an art that was almost entirely forgotten. With the sole intent of documenting and then reviving it, he travelled across war torn Cambodia by foot from village to village, without so much as map, asking if silk weaving still occurred.

It was one of these villages that saved his life when at one point he came into contact with Khmer Rouge soldiers. Standing on the opposite bank of the river soldiers pointed at him with their guns, and it was not until the village surrounded him that they finally put them down.

In 2002 Morimoto started the Project Wisdom from the Forest. He bought up a 5 hectare plot to recreate an ancestral forest with all the plants required to breed silk and create natural colour dyes.

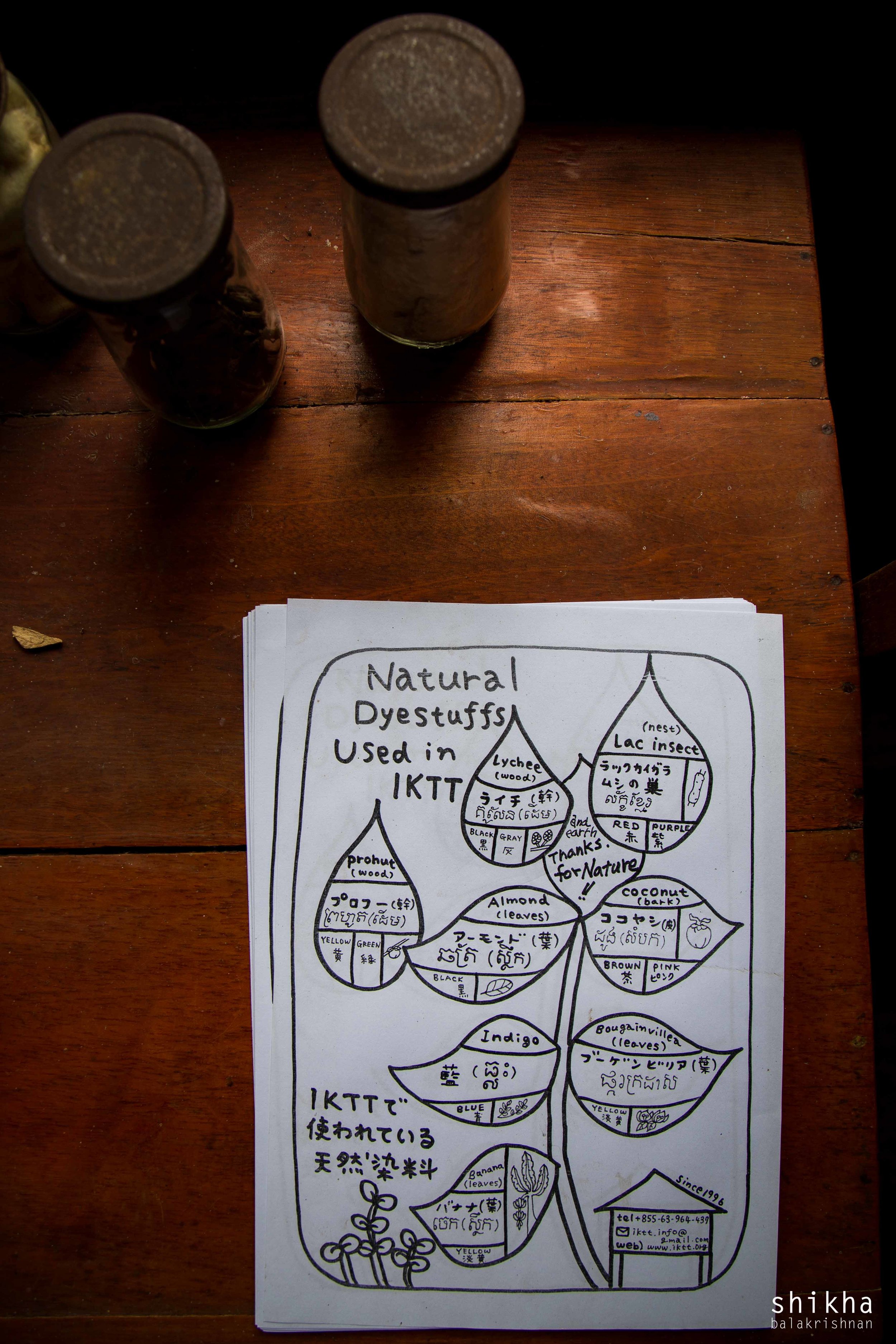

Today the forest has grown to 23 hectares. A self-sustaining textile village is now home to 160 people who live and work there. Every strand of thread woven here passes through human hands. Every dye used to colour the golden yarn is grown in the forest. Red comes from the nest of the lac insect, Black from Indian almond leaves, Blue from indigo, Orange from the centre of the Annato Plant, Yellow and Green from the bark of the native Prohut tree and Grey from the wood of the lychee tree.

When you look at the muted silks draped over the wooden stand and kept in a dark corner, its easy to forget it’s ancient origins, tumultuous history and the perseverance of one man in preserving this craft from disappearing.